MARKETING MANAGEMENT - Pricing Decisions

Product costs - Pricing Decisions

Posted On :

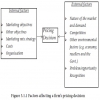

Costs may be classified as variable, fixed and semi-fixed. Take the case of an airline.

Product costs

Costs may be classified as variable, fixed and semi-fixed. Take the case of an airline. It may consider the annual depreciation on an aircraft as a fixed cost. Taking the plane off the ground to fly from one city to another incurs certain semi-fixed costs like the fuel, the compensation of flight personnel, the airport fees and so on. These costs are approximately the same for any given flight whether the plane is empty, half-loaded or completely full of passengers. The variable costs of the flight would include primarily the costs of food and beverage. They vary directly with the number of passengers.

If fixed and semi-fixed costs make up a larger portion of total costs, as in the airline example, pricing to get maximum capacity utilization is crucial. Until the seller covers fixed costs, money is lost. After fixed costs are covered, each incremental sale contributes proportionally large amounts to profits.

If variable costs are a relatively high percentage of total costs (which is quite likely in many manufacturing firms), pricing to maximize unit contribution (i.e. the difference between the unit variable cost and price) will be critical to profitability. Under these cost conditions, the manufacturer would naturally work to maximize unit prices and to reduce variable costs.

Above are two examples. In the first one, the objective of the airline’s pricing strategy will be to generate enough total revenue to cover its fixed costs and above that to get maximum capacity utilization to make profits. In the second one, a manufacturer will price to cover its high variable costs per unit and get enough contribution to amortize fixed costs and make a profit.

Under certain conditions, firms may elect to price at less than full cost. In conditions of capacity underutilization, for instance, firms with high fixed costs may take business at prices that cover variable costs and make some incremental contribution to fixed costs (or overheads). The idea is to get through bad times, keep the factory running and hold some critical team of managers, skilled technicians and labour.

Pricing temporarily at less than full cost may also be used as a strategy to get a particularly large order. The expectation is that by taking the business, the firm may be able to reduce its unit costs and/or later raise its prices so as to make a profit on subsequent orders. Taking business below cost with the hope of offsetting near-term losses with longer-term profits may be a risky tactic, since there is no assurance that the losses can be made up.

Pricing near or below cost may also be done to gain a large market share. Generally pricing low to preempt market share is predicted on the assumption that unit costs will come down significantly as volume increases. This may happen through gaining manufacturing experience.

In fact, in many firms, a so-called experience or learning curve is used to calculate what the effect will be of volume growth on unit costs. To a large extent, learning curve experience reduces the variable cost component of unit costs. Labour gains in efficiency and purchases of materials and parts in larger volumes all result in lower prices and manufacturing process improvements produce cost savings.

Indeed, the fixed-cost component of unit costs may also come down with volume increases. Larger plants may be more cost efficient. Large-scale selling and advertising programs may also be more cost efficient. If product sales are particularly sensitive to heavy advertising, or the product requires widespread distribution or extensive field service support, fixed marketing expenditures for these purposes must usually be at a high level.

These so-called scale economies come in certain cost categories depending on the product, the processes used to manufacture it and the level of marketing spending required to be competitive. If significant scale economies are achievable, some competitors may be willing to price low enough to gain volume, thus preventing other competitors from going down the learning curve and hoping to emerge as low-cost producers with dominant market shares.

Product cost, then, is not a simple ‘hard’ number. How cost is calculated for pricing purposes is a matter of managerial judgment. It may be construed as full cost or as variable cost. It may be the cost levels being experienced or experience curve estimates of future costs. The interpretation of cost factors for pricing will depend greatly on product/ market objectives.

Costs may be classified as variable, fixed and semi-fixed. Take the case of an airline. It may consider the annual depreciation on an aircraft as a fixed cost. Taking the plane off the ground to fly from one city to another incurs certain semi-fixed costs like the fuel, the compensation of flight personnel, the airport fees and so on. These costs are approximately the same for any given flight whether the plane is empty, half-loaded or completely full of passengers. The variable costs of the flight would include primarily the costs of food and beverage. They vary directly with the number of passengers.

If fixed and semi-fixed costs make up a larger portion of total costs, as in the airline example, pricing to get maximum capacity utilization is crucial. Until the seller covers fixed costs, money is lost. After fixed costs are covered, each incremental sale contributes proportionally large amounts to profits.

If variable costs are a relatively high percentage of total costs (which is quite likely in many manufacturing firms), pricing to maximize unit contribution (i.e. the difference between the unit variable cost and price) will be critical to profitability. Under these cost conditions, the manufacturer would naturally work to maximize unit prices and to reduce variable costs.

Above are two examples. In the first one, the objective of the airline’s pricing strategy will be to generate enough total revenue to cover its fixed costs and above that to get maximum capacity utilization to make profits. In the second one, a manufacturer will price to cover its high variable costs per unit and get enough contribution to amortize fixed costs and make a profit.

Under certain conditions, firms may elect to price at less than full cost. In conditions of capacity underutilization, for instance, firms with high fixed costs may take business at prices that cover variable costs and make some incremental contribution to fixed costs (or overheads). The idea is to get through bad times, keep the factory running and hold some critical team of managers, skilled technicians and labour.

Pricing temporarily at less than full cost may also be used as a strategy to get a particularly large order. The expectation is that by taking the business, the firm may be able to reduce its unit costs and/or later raise its prices so as to make a profit on subsequent orders. Taking business below cost with the hope of offsetting near-term losses with longer-term profits may be a risky tactic, since there is no assurance that the losses can be made up.

Pricing near or below cost may also be done to gain a large market share. Generally pricing low to preempt market share is predicted on the assumption that unit costs will come down significantly as volume increases. This may happen through gaining manufacturing experience.

In fact, in many firms, a so-called experience or learning curve is used to calculate what the effect will be of volume growth on unit costs. To a large extent, learning curve experience reduces the variable cost component of unit costs. Labour gains in efficiency and purchases of materials and parts in larger volumes all result in lower prices and manufacturing process improvements produce cost savings.

Indeed, the fixed-cost component of unit costs may also come down with volume increases. Larger plants may be more cost efficient. Large-scale selling and advertising programs may also be more cost efficient. If product sales are particularly sensitive to heavy advertising, or the product requires widespread distribution or extensive field service support, fixed marketing expenditures for these purposes must usually be at a high level.

These so-called scale economies come in certain cost categories depending on the product, the processes used to manufacture it and the level of marketing spending required to be competitive. If significant scale economies are achievable, some competitors may be willing to price low enough to gain volume, thus preventing other competitors from going down the learning curve and hoping to emerge as low-cost producers with dominant market shares.

Product cost, then, is not a simple ‘hard’ number. How cost is calculated for pricing purposes is a matter of managerial judgment. It may be construed as full cost or as variable cost. It may be the cost levels being experienced or experience curve estimates of future costs. The interpretation of cost factors for pricing will depend greatly on product/ market objectives.

Tags : MARKETING MANAGEMENT - Pricing Decisions

Last 30 days 541 views